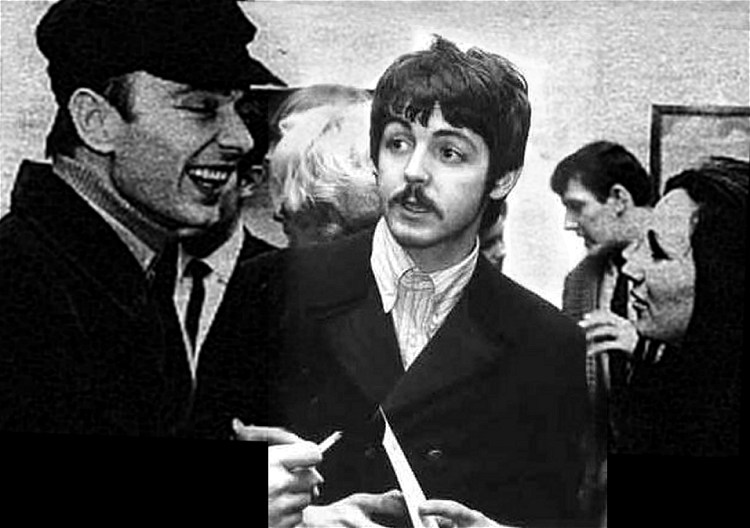

Paul McCartney and Brian Epstein discuss The Beatles’ third film with Joe Orton

English playwright Joe Orton had been asked by Walter Shenson, producer of the films A Hard Day's Night and Help!, to come up with a script for The Beatles' third film.

Shenson asked Orton to rework a draft script by an unknown writer. Orton used portions of the earlier script and incorporated new scenes. The result was Up Against It, which in 1967 was briefly considered as the group's cinematic follow-up to Help!.

Orton began writing Up Against It on January 16th. A contract was drawn up, which allowed Orton to buy back the script rights were it to be rejected.

On this day Orton met Paul McCartney and Brian Epstein to discuss the project. The meeting took place at Epstein's London mews house.

I rang the bell and an old man opened the door. He seemed surprised to see me. 'Is this Brian Epstein's house?' I said. 'Yes, sir,' he said, and led the way into the hall. I suddenly realised that the man was the butler. I've never seen one before. He took my coat and I went to the lavatory. When I came out he'd gone. There was nobody about. I wandered around a large dining-room which was laid for dinner. And then I got to feel strange. The house appeared to be empty. So I went upstairs to the first floor. I heard music only I couldn't decide where it came from. So I went further upstairs and found myself ina bedroom. I came down again and found the butler. He took me into a room and said in a loud voice, 'Mr Orton.'Everybody looked up and stood to their feet. I was introduced to one or two people. And Paul McCartney. He was just as the photographs. Only he'd grown a moustache. His hair was shorter too. He was playing the latest Beatles recording, Penny Lane. I liked it very much. Then he played the other side Strawberry something. I didn't like this as much. We talked intermittently. Before we went out to dinner we'd agreed to throw out the idea of setting the film in the thirties. We went down to dinner. The crusted old retainer - looking too much like a butler to be good casting - busied himself in the corner.

'The only thing I get from the theatre,' Paul M. said, 'is a sore arse.' He said Loot was the only play he hadn't wanted to leave before the end. 'I'd've liked a bit more,' he said. We talked of the theatre. I said that compared to the pop scene the theatre was square. 'The theatre started going downhill when Queen Victoria knighted Henry Irving,' I said. 'Too fucking respectable.'

We talked of drugs, of mushrooms which give hallucinations - like LSD. 'The drug, not the money,' I said. We talked of tattoos. And, after one or two veiled references, marijuana. I said I'd smoked it in Morocco. The atmosphere relaxed a little. Dinner ended and we went upstairs again. We watched a programme on TV. It had phrases in it like 'the in-crowd' and 'swinging London'.

There was a scratching at the door. I thought it was the old retainer, but someone got up to open the door and about five very young and pretty boys trooped in. I rather hoped this was the evening's entertainments. It wasn't, though. It was a pop group called The Easybeats. I'd seen them on TV. I liked them very much then. In a way they were better (or prettier) offstage than on.

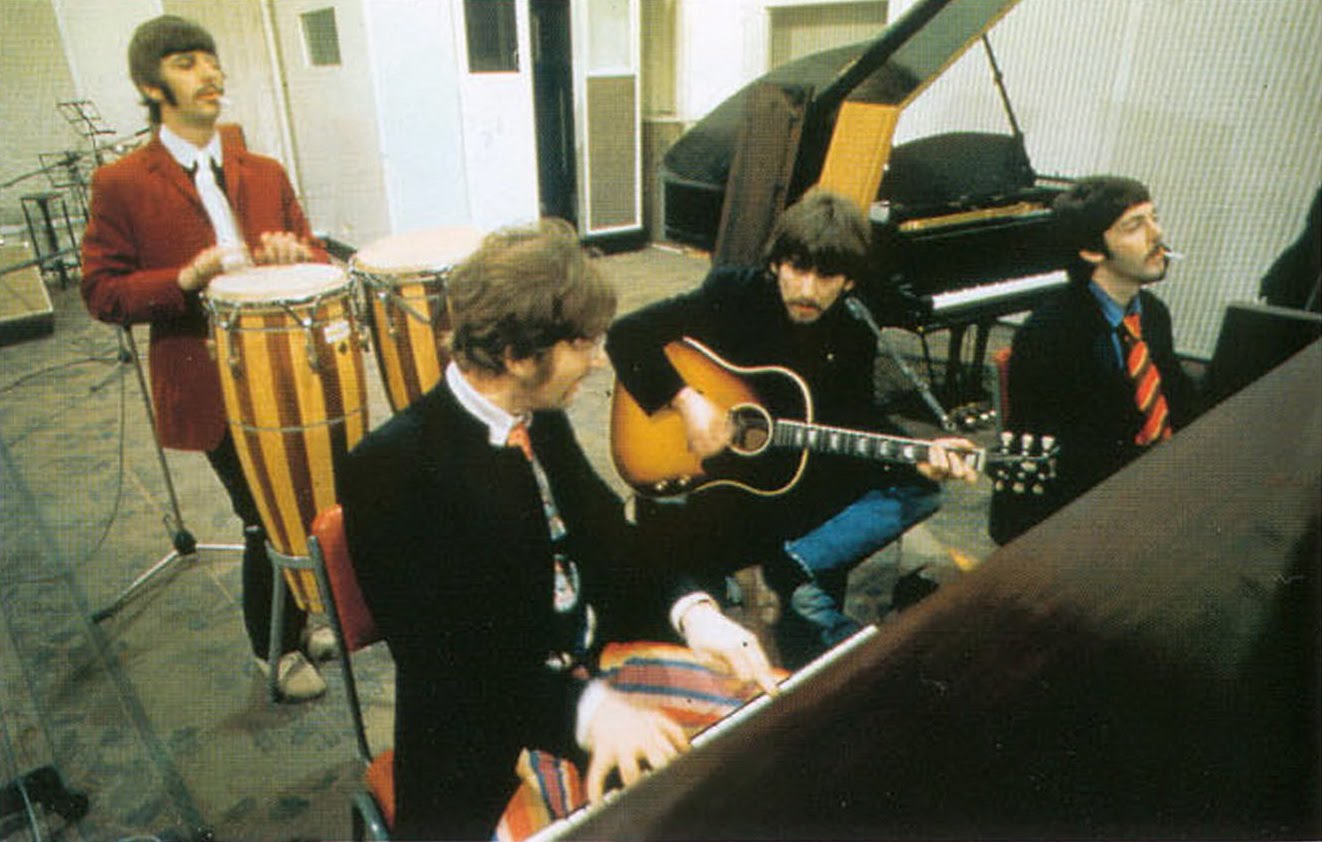

After a while Paul McCartney said, 'Let's go upstairs'. So he and I and Peter Brown went upstairs to a room also fitted with a TV ... A French photographer arrived with two beautiful youths and a girl. He'd taken a set of new photographs of The Beatles. They wanted one to use on the record sleeve. Excellent photograph. And the four Beatles look different with their moustaches. Like anarchists in the early years of the century.

After a while we went downstairs. The Easybeats still there. The girl went away. I talked to the leading Easybeat. Feeling slightly like an Edwardian masher with a Gaeity Girl. And then I came over tired and decided to go home. I had a last word with Paul M. 'Well,' I said, 'I'd like to do the film. There's only one thing we've got to fix up.' 'You mean the bread.' 'Yes.' We smiled and parted. I got a cab home. It was pissing down.

The Orton Diaries, 1986

Orton delivered his first draft of Up Against It on February 25th. The Beatles and Epstein decided it was be too risqué and the project was abandoned, although Orton was well paid for his efforts. The script was returned to Orton without comment.

The reason why we didn't do Up Against It wasn't because it was too far out or anything. We didn't do it because it was gay. We weren't gay and really that was all there was to it. It was quite simple, really. Brian was gay...and so he and the gay crowd could appreciate it. Now, it wasn't that we were anti-gay - just that we, The Beatles, weren't gay.

Other film ideas considered by The Beatles at this time included adaptations of Lord Of The Rings and The Three Musketeers, but like Up Against It all were dropped.